Constable’s printed landscapes

by Elenor Ling

In 1829 John Constable took on a young printmaker to engrave a series of prints after his own works, which would become known as ‘English Landscape’.

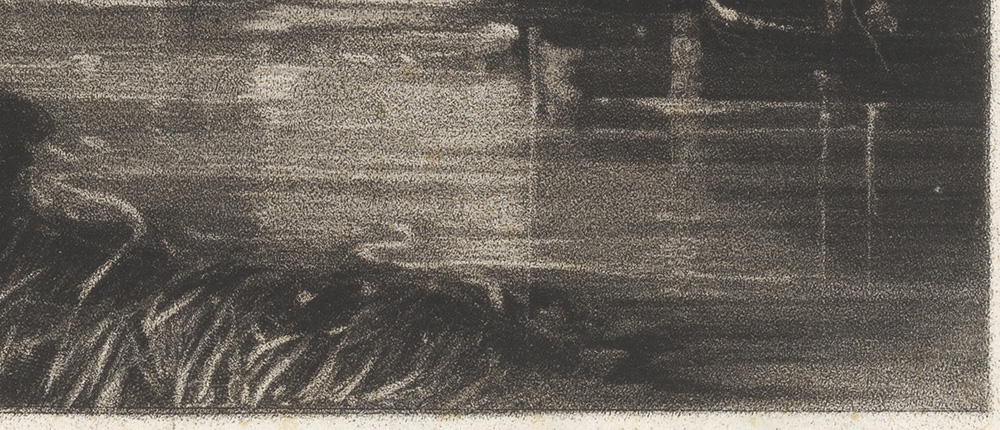

The printmaker was David Lucas (1802–1881), and he specialised in a technique called mezzotint, whereby images are composed of tone, in a network of tiny dots, with light picked out of darkness. The printmaker has a laborious start. S/he pits surface of a metal plate repeatedly with a tool called a rocker. Each of these tiny pits will hold printing ink, and first the plate must be evenly and fully rocked. Printed at that point impressions would be entirely black, so to achieve an image the printmaker scrapes and polishes the surface, reducing or removing the pits, creating areas of varying, velvety tone.

The two men worked in close collaboration: Lucas would adapt and realise Constable’s works onto steel plates, and pull proof impressions to send to his employer. Constable returned them with instructions for changes, sometimes drawing on or daubing an impression to emphasise what he meant. Some directives would be specific (‘sun cleared around its orb’) while others were a little more vague (‘the shower a little darker here & there’), or even quite poetic (‘rays of light crushed’), revealing the heightened, intuitive bond the artists came to achieve.

Mezzotint was ideal for Constable’s purpose in that not only were incredibly subtle variations of tone possible, but the images were easily editable. Unlike other printmaking techniques, where it is more difficult to make changes without leaving tell-tale traces, in mezzotint Lucas was able to transform an image while retaining its freshness.

What were the landscapes? Twenty-two subjects were eventually chosen, published in five parts between June 1830 and July 1832, each containing four plates except the last, which contained six. There were later editions, with slight changes to the number and order of the plates, but the history is a little too complicated for the scope this post!

What’s interesting is that when Constable spoke and wrote on the topic of landscape later in life, he used many of these East-Anglian scenes in an all-encompassing way, to ‘characterise the scenery of England’. That was how he introduced the prints on the set’s title page: ‘VARIOUS SUBJECTS OF / LANDSCAPE / CHARACTERISTIC OF ENGLISH SCENERY…’ Just over half the plates, however, were Suffolk/Essex subjects, mostly around Constable’s birthplace in East Bergholt and hardly representative of the whole country.

However, the locations are not (and would not have been) obvious to anyone unfamiliar with the areas. The scene of a common in East Bergholt with his father’s flour mill, in which Constable had worked and knew intimately, is given only a general title, ‘Spring’; the same is true of many others - ‘Autumnal Sun Set’, ‘Noon’ and ‘Summer Afternoon – After a Shower’. They are characteristic of something else entirely: of seasons, times of day and states of weather. Constable had made it his life’s work to study landscape through close observation of natural phenomena, and these temporal and atmospheric concerns were important to him, much more so than producing a set of illustrative, picturesque views.

To be continued…